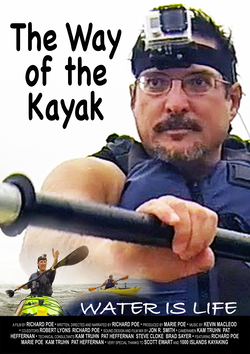

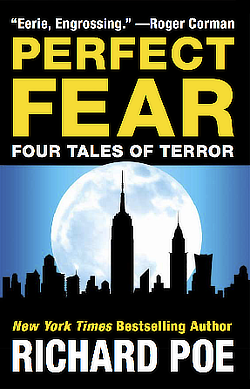

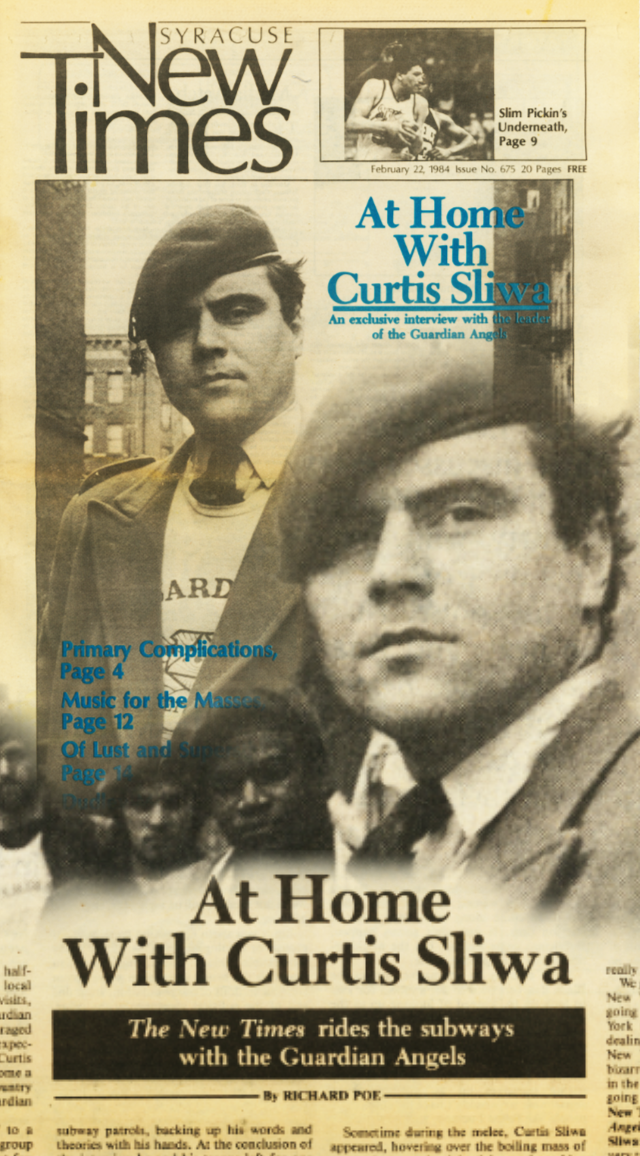

Richard Poe Interviews Curtis Sliwa (February 22, 1984)

Richard Poe Interviews Curtis Sliwa, February 22, 1984 Commentary: Curtis Sliwa’s Dilemma, June 27, 1984 Press Club Award for Curtis Sliwa Coverage, November 19, 1984 |

Richard Poe

WITH AN ENDORSEMENT from Rudy Giuliani, Curtis Sliwa is well on his way to becoming the next mayor of New York City. But, back in 1984, Curtis was a controversial figure, leading a rag-tag band of volunteer crimefighters called The Guardian Angels, whom many denounced as “vigilantes.” As a young journalist, just starting my first newspaper job at The Syracuse New Times, I championed Curtis, predicting he was destined for greater things. In November, 1984, the Syracuse Press Club—the leading association for professional journalists in Central New York—honored me with an award for my Guardian Angels coverage. — RICHARD POE, Sept. 5, 2021 |

The New Times Rides the Subways with the Guardian Angels

BY RICHARD POE

The Syracuse New Times, February 22, 1984, pages 1, 8-9

AFTER MONTHS of speculation, half-hearted acquiescence from local politicians and exploratory visits, it’s finally official: The Guardian Angels are coming to Syracuse. Encouraged by Police Chief Thomas Sardino’s unexpectedly warm welcome, Angels’ founder Curtis Sliwa says he hopes “Syracuse will become a prototype for other cities around the country [in] embracing the concept of the Guardian Angels.”

While declining to commit himself to a precise timetable, Sliwa promises the group will begin recruiting here within the next few weeks.

The gaudily attired Angels, whose flamboyant style evolved from the “colors” worn by youth gangs in New York City, will no doubt be conspicuous pedestrians on the streets of Syracuse. And while Sliwa insists that the “true success” of his patrols has only been realized through their expansion into the smaller cities and towns of grass-roots America, the Guardian Angels have nevertheless retained, both in their style and social philosophy, the unmistakable imprint of the South Bronx neighborhoods from which they sprang.

| New York is just too wild. We’re dealing with wartime conditions down here. New York is la-la land, the land of the bizarre, the Beirut of the United States. It’s in the smaller towns like Syracuse that we’re going to make a difference.. |

The New Times interviewed Curtis Sliwa at the Guardian Angels’ new Harlem headquarters, an abandoned building at 124th Street and Lexington Avenue. For three hours, Sliwa discussed everything from urban overcrowding to the history of the Black Panther Party, which he regards as a forerunner of his own organization. Sliwa’s breath froze as he spoke. At the time, the building had no heat, and Guardian Angels huddled around a space heater in the next room, much as outside, on the other side of the street, people gathered around burning trashcans to warm their hands.

Amid such urban devastation the red berets, fatigues and combat boots of the Guardian Angels took on a disturbingly paramilitary appearance, as if the gloomy Harlem neighborhood, with its boarded-up windows and charred, battered storefronts, had already become a battle zone in some futuristic guerrilla war.

At 6-foot-1, Sliwa towers over most of his troops. The former McDonald’s manager exudes a toughness and self-confidence that put him at home in any surroundings, whether dispatching patrols amid the din and bustle of Grand Central Station or fielding questions before a forest of microphones and camera lenses. Throughout the interview, Sliwa continued to discharge his duties, greeting and debriefing incoming detachments of Guardian Angels and every few minutes answering emergency phone calls from patrols still out on the streets.

Despite his pressing administrative responsibilities, Sliwa continues to lead nightly subway patrols, backing up his words and theories with his hands. At the conclusion of the interview he and his troops left for one such patrol. The Angels boarded the train at 125th Street. In standard fashion, the Guardian Angels split up among the different cars, communicating with each other through the connecting windows using special hand signals. Two transit officers were on duty in one of the cars. As Sliwa passed down the aisle, one of the cops looked after him, his lips curled in disgust, and snorted. The other simply shook his head.

For most of the ride, a single Guardian Angel remained in the car, a tall, dark-skinned youth of 16 or 17 who leaned sullenly against the door, casting occasional side-long looks at the officers at the other end of the car. Most of the passengers simply stared into space, oblivious to all of it.

At 86th Street, five or six drunken preppies, who looked like they had just stumbled out of a fraternity party, entered the train. There three officers now, standing by the door. The preppies blocked the door and began shouting to their friends at the turnstiles to hurry up, ignoring requests by the police to stand clear and let the doors close.

A shoving match ensued, during which one of the preppies took a swing at a patrolman. Within seconds, the transit police had subdued the students, dragging away three of them in handcuffs.

Sometime during the melee, Curtis Sliwa appeared, hovering over the boiling mass of arms, legs, and nightsticks and making conciliatory gestures, but refraining from jumping into the fray. As the doors finally closed, and the train ground into motion, Sliwa watched out the window as the officers led their prisoners away.

Sliwa says relations between the Guardian Angels and the Metropolitan Transit Police are poor. In another incident, earlier that evening, two transit officers refused to allow a platoon of Guardian Angels to form up on one of the platforms in Grand Central subway station. They claimed the Angels were blocking traffic.

“It’s not enough that we have to fight criminals,” Sliwa complained at the time, “but then we have the cops on our backs too. They’re a big pain in our Achilles’ heel.”

New Times: Why have you decided to start a chapter in Syracuse?

Sliwa: We’ve been receiving inquiries from individuals in Syracuse almost ever since we were founded, whether from concerned students, merchants or just average citizens.

A lot of people have the misconception that the Guardian Angels are strictly a big-city phenomenon. But I think our true success has been our expansion into smaller cities and towns, like Syracuse, where we can concentrate on a few key trouble spots and really make an impact.

We get a lot more applause for our work in New York City, but the fact is, we’re not going to change anything down here. New York is just too big and too wild. We’re dealing with wartime conditions down here. New York is la-la land, the land of the bizarre, the Beirut of the United States. It’s in the smaller towns like Syracuse that we’re going to make a difference.

New Times: What changes can the Guardian Angels bring about in Syracuse?

Sliwa: The situation on Marshall Street is very typical of what we find in a lot of cities. Here we have the Dome, which is a big moneymaker for the city, we have all these expensive shops, cafes and bistros, all these attractions for the middle class. It’s a showcase for the city, their pride and joy. They’re trying to create a city within a city, a little insulated haven for the students, so they can do all their shopping and partying in one place, without ever having to rub shoulders with the locals. That way the parents will feel secure about leaving their little boys and girls alone in the city.

But on the other hand, Marshall Street is a public thoroughfare. The local people from the projects want to come up there and hang out too. So you get locals being harassed by the cops, by campus security, you get friction between students and townies.

When we start setting up patrols, we’ll recruit people from the student community and the inner-city both, and they’ll share the responsibilities of patrolling all areas of the city, together. The students will have to learn that they don’t live in Shangri-la, that they’re a part of the community too, and if they want to do something about the crime and violence, they’ll have to do it by working with their neighbors instead of against them.

New Times: And will this really have a significant effect on the dynamics of Marshall Street?

Sliwa: Let’s be realistic. What’s happening on Marshall Street is not an isolated event. Regentrification is happening all over the country, resettling the middle class in the city, and pushing the poor people out. Just look around you here in New York. Everywhere you look, redevelopment, rezoning, evictions. Ten years down the line, Manhattan will be an island of the rich, nothing but financial centers, malls, giant high-rises, condominiums. The poor people will have to go somewhere else.

I’m opposed to regentrification, but the Guardian Angels aren’t going to stop it. It’s too big. It won’t help for everyone to put on a red beret and go out on safety patrols. But I would like to think that our example inspires others to mobilize and organize, that we’re acting as a catalyst, establishing a tradition of self-help that others will follow.

New Times: What kind of reception have the Guardian Angels gotten from the minority community?

Sliwa: I think that when we first got started, there was a certain amount of suspicion from the black community. But once they saw what we were actually doing, the attitude changed.

As it stands now, the racial breakdown in our New York City chapter is 65 percent Hispanic, 30 percent black and 5 percent white, and that’s more or less duplicated throughout the East Coast. I would go so far as to say that, without the initial support of the Hispanic community, there would be no Guardian Angels today. We got a lot of help from Hispanic businesses, from the Spanish-language media—papers like El Diario La Prensa, Noticias del Mundo, Hispanic radio stations. I think a big part of the reason for that is that Hispanics are more group-oriented, whether it’s social clubs, church clubs, boys’ clubs, even youth gangs, there’s more of a tendency to get organized. There’s also the machismo factor, the idea of protecting women, children, the elderly. Out of all the cultures, the Guardian Angels’ greatest appeal is to Hispanics.

As for the poor turnout among whites, well, whites tend to be less group conscious, more independent. There’s also the middle-class attitude, not wanting to take the risk, get a mar on your record. Let’s face it, being in the Guardian Angels ain’t gonna help your resume.

It’s a little different out West. On the West Coast, the breakdown is 40 percent Hispanic, 30 percent black, 30 percent white. Whites on the West Coast are more open to community organizing, whether it’s communes, environmental groups, or the National Rifle Association. So the predominance of minorities is a little bit less, but it’s still there.

New Times: For many people, the sight of uniformed, paramilitary patrols of minority youths brings back memories of the black- and brown-power movements of the Sixties. How do the Guardian Angels fit into that tradition, if at all?

Sliwa: I was talking to Felipe Luciano the other day, the former leader of the Young Lords, and he said that he felt the Guardian Angels were, in many ways, carrying out the same work that groups like the Young Lords and the Black Panthers did in the Sixties. We’re telling people to organize in their own neighborhoods, to help themselves, rather than depend on politicians or authority figures. Like the Panthers, we believe that every-day people can do something about the situation in our cities.

When you see neighborhoods like this one, with the drugs, the violence, the prostitution, you realize that it’s really a kind of genocide. People’s minds are being destroyed—their lives and hope—and the system is unwilling or unable to do anything about it. People have to stop waiting for the great white knight to come along every four years at election time. It just ain’t gonna happen. Politicians come and go, but the neighborhoods just keep getting worse.

We’re offering an alternative, just as the Black Panthers tried to do, a model for kids to look up to, instead of looking up to the pimps, pushers and hoodlums. I have to admit, the pimps and pushers still have more status in this neighborhood than we do. But we’re respected when we walk down the street. It’s not like being a cop. If we were setting ourselves up as another police department we wouldn’t have the support of people like Felipe Luciano, and we wouldn’t have someone like Lester Dixon, a former Black Panther, heading our chapter in San Francisco.

New Times: Do you really believe that the Guardian Angels can succeed where the Black Panthers failed?

Sliwa: I think so. The Black Panthers were different from us in a lot of ways. For one thing, they were putting forth a revolutionary ideology of black power, directly challenging the system. And they were not averse to taking up arms to defend their people.

The Guardian Angels, on the other hand, will never bear arms. I just don’t believe in it. Even more important, we’re not directly confronting the powers-that-be. We have a white person, myself, at the forefront of the movement, which is much easier for the establishment to accept. And our group is interracial and cross sectional. Everyone in the city is affected by crime—blacks, whites, people from downtrodden areas, people from nice areas, in-between areas. There’s no safe haven.

I think the bottom line is that we just have too broad a base of support. The Guardian Angels are accepted in little towns, big towns, by all races and creeds, on the left and on the right. The public likes us. For that reason, I think we actually pose more of an overall threat than the Panthers ever did; but the politicians are only just now beginning to realize that. They’re learning that if they get into an adversary relationship with the Guardian Angels, it’s going to be bad for their careers, because the public is behind us.

New Times: Have the Guardian Angels met with any organized opposition?

Sliwa: Whenever we set up somewhere, there’s always the initial opposition from the cops, city officials, what have you. They say we’re not needed, call us vigilantes, that kind of thing.

But if you mean opposition from political groups or ideologies, no. One of the really remarkable things about the Guardian Angels is the broad acceptance we’ve gotten from all sections of the population, from one end of the political spectrum to the other. You just can’t argue with our goals: protecting innocent people.

Actually, there was one incident that happened in April 1982, when we set up in Windsor, Canada. It was our first chapter in Canada, and it was getting a lot of press. Well, the Communist Workers’ Party, which had never said a word against us when we were in the United States, decided that this was their chance to get in on some of the publicity. So when we went on our first patrol in Windsor, we were met by a counterdemonstration of CWP members, with placards and everything. They pelted us with rocks, tomatoes, eggs, shouted a lot of abuse at us. The basic drift was that we were some kind of fascist, brownshirt organization. They called us “Reagan’s Youth,” you know, comparing us to Hitler’s Youth, and said we were agents of U.S. Imperialism. It was just a one-day thing. When we set up in other Canadian cities—Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver—there was no problem.

New Times: One last question: A lot of people have expressed the suspicion that you are only using the Guardian Angels as a vehicle for your own political ambitions.

Sliwa: I think if you really look at the person who is Curtis Sliwa, you’ll realize that I don’t need the Guardian Angels to help me run for office. If that’s what I wanted, I could do it on my own merits. But for me to do that would be a repudiation of everything that I stand for. Here I am trying to arouse people to stand up for themselves, and not rely on politicians. If all of a sudden I tried to set myself up as a political figure, I’d be just as guilty of perpetuating that same apathetic attitude. Elections just aren’t going to do it. Self-help will.