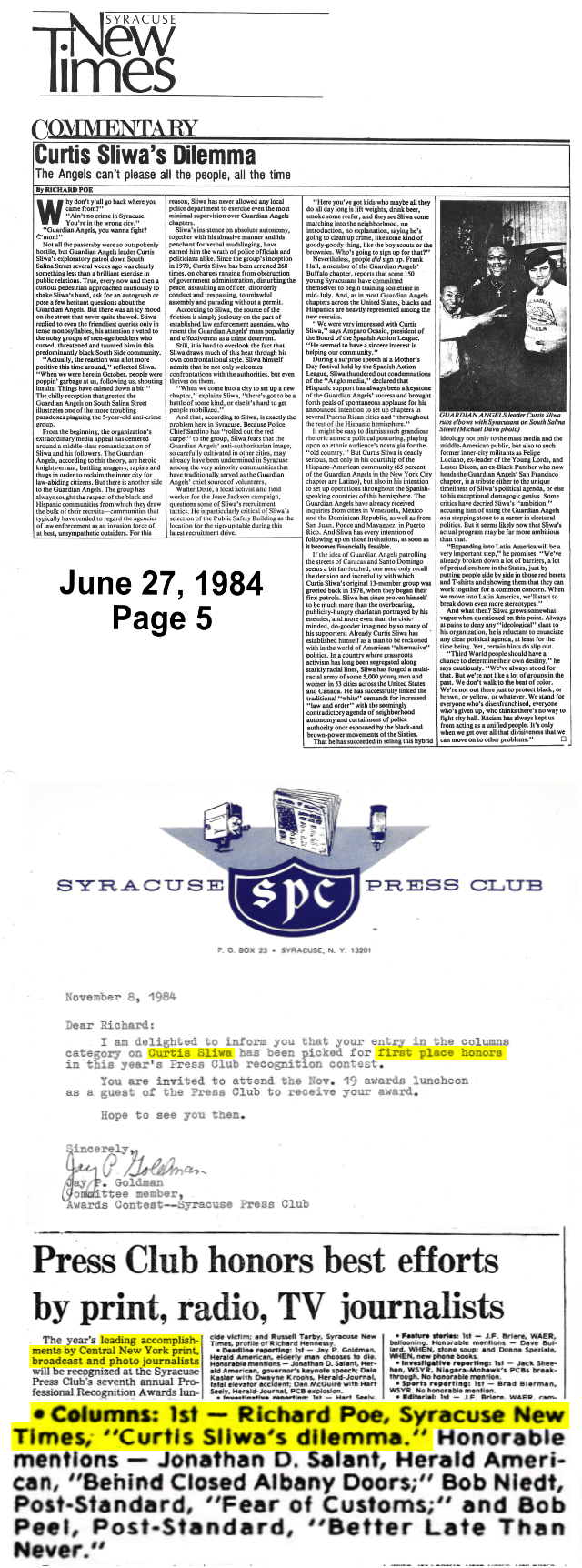

COMMENTARY: Curtis Sliwa’s Dilemma (June 27, 1984)

Richard Poe Interviews Curtis Sliwa, February 22, 1984 Commentary: Curtis Sliwa’s Dilemma, June 27, 1984 Press Club Award for Curtis Sliwa Coverage, November 19, 1984 |

Richard Poe

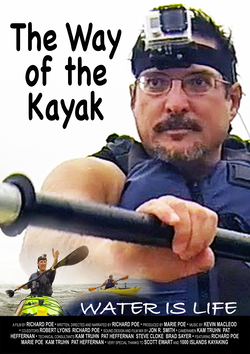

I’LL NEVER FORGET my first glimpse of the Guardian Angels in the early ’80s. Entering a subway station in white t-shirts and red berets, they looked like a street gang, but the crowd cheered and applauded them like heroes. Later, I learned they were a volunteer crime-fighting group led by Brooklyn-born Curtis Sliwa. In 1984, when Curtis announced he was launching a Guardian Angels chapter in my hometown of Syracuse, New York, many of my colleagues were skeptical, but I gave Curtis positive coverage in the local press. To my surprise, the Syracuse Press Club honored me with an award for my Guardian Angels coverage. — RICHARD POE, Sept. 5, 2021 |

The Angels Can’t Please All the People, All the Time

BY RICHARD POE

The Syracuse New Times, June 27, 1984, pages 5

WHY DON’T y’all go back where you came from?”

“Ain’t no crime in Syracuse. You’re in the wrong city.”

“Guardian Angels, you wanna fight? C’mon!”

Not all the passersby were so outspokenly hostile, but Guardian Angels leader Curtis Slia’s exploratory patrol down South Salina Street several weeks ago was clearly something less than a brilliant exercise in public relations. True, every now and then a curious pedestrian approached cautiously to shake Sliwa’s hand, ask for an autograph or pose a few hesitant questions about the Guardian Angels. But there was an icy mood on the street that never quite thawed. Sliwa replied to even the friendliest queries only in tense monsyllables, his attention riveted to the noisy groups of teen-age hecklers who cursed, threatened and taunted him in this predominantly black South Side community.

“Actually, the reaction was a lot more positive this time around,” reflected Sliwa. “When we were here in October, people were poppin’ garbage at us, following us, shouting insults. Things have calmed down a bit.”

The chilly reception that greeted the Guardian Angels on South Salina Street illustrates one of the more troubling paradoxes plaguing the 5-year-old anti-crime group.

|

Sliwa himself admits that he not only welcomes confrontations with the authorities, but even thrives on them. “When we come into a city to set up a new chapter,” explains Sliwa, “there’s got to be a battle of some kind, or else it’s hard to get people mobilized.” |

From the beginning, the organization’s extraordinary media appeal has centered around a middle-class romanticization of Sliwa and his followers. The Guardian Angels, according to this theory, are heroic knights-errant, battling muggers, rapists and thugs in order to reclaim the inner city for law-abiding citizens. But there is another side to the Guardian Angels. The group has always sought the respect of the black and Hispanic communities from which they draw the bulk of their recruits—communities that typically have tended to regard the agencies of law enforcement as an invasion force of, at best, unsympathetic outsiders. For this reason, Sliwa has never allowed any local police department to exercise even the most minimal supervision over Guardian Angels chapters.

Sliwa’s insistence on absolute autonomy, together with his abrasive manner and his penchant for verbal mudslinging, have earned him the wrath of police officials and politicians alike. Since the group’s inception in 1979, Curtis Sliwa has been arrested 268 times, on charges ranging from obstruction of government administration, disturbing the peace, assaulting an officer, disorderly conduct and trespassing, to unlawful assembly and parading without a permit.

According to Sliwa, the source of the friction is simply jealousy on the part of established law enforcement agencies, who resent the Guardian Angels’ mass popularity and effectiveness as a crime deterrent.

Still, it is hard to overlook the fact that Sliwa draws much of this heat through his own confrontational style. Sliwa himself admits that he not only welcomes confrontations with the authorities, but even thrives on them.

“When we come into a city to set up a new chapter,” explains Sliwa, “there’s got to be a battle of some kind, or else it’s hard to get people mobilized.”

And that, according to Sliwa, is exactly the problem here in Syracuse. Because Police Chief Sardino has “rolled out the red carpet” to the group, Sliwa fears that the Guardian Angels’ anti-authoritarian image, so carefully cultivated in other cities, may already have been undermined in Syracuse among the very minority communities that have traditionally served as the Guardian Angels’ chief source of volunteers.

Walter Dixie, a local activist and field worker for the Jesse Jackson campaign, questions some of Sliwa’s recruitment tactics. He is particularly critical of Sliwa’s selection of the Public Safety Building as the location for the sign-up table during his latest recruitment drive.

“Here you’ve got kids who maybe all they do all day long is lift weights, drink beer, smoke some reefer, and they see Sliwa come marching into the neighborhood, no introduction, no explanation, saying he’s going to clean up crime, like some kind of goody-goody thing, like the boy scouts or the brownies. Who’s going to sign up for that?”

Nevertheless, people did sign up. Frank Hall, a member of the Guardian Angels’ Buffalo chapter, reports that some 150 young Syracusans have committed themselves to begin training sometime in mid-July. And, as in most Guardian Angels chapters across the United States, blacks and Hispanics are heavily represented among the new recruits.

“We were very impressed with Curtis Sliwa,” says Amparo Ocasio, president of the Board of the Spanish Action League. “He seemed to have a sincere interest in helping our community.”

During a surprise speech at a Mother’s Day festival held by the Spanish Action League, Sliwa thundered out condemnations of the “Anglo media,” declared that Hispanic support has always been a keystone of the Guardian Angels’ success and brought forth peals of spontaneous applause for his announced intention to set up chapters in several Puerto Rican cities and “throughout the rest of the Hispanic hemisphere.”

It might be easy to dismiss such grandiose rhetoric as mere political posturing, playing upon an ethnic audience’s nostalgia for the “old country.” But Curtis Sliwa is deadly serious, not only in his courtship of the Hispano-American community (65 percent of the Guardian Angels in the New York City chapter are Latino), but also in his intention to set up operations throughout the Spanish-speaking countries of this hemisphere. The Guardian Angels have already received inquiries from cities in Venezuela, Mexico and the Dominican Republic, as well as from San Juan, Ponce and Mayaguez, in Puerto Rico. And Sliwa has every intention of following up on those invitations, as soon as it becomes financially feasible.

If the idea of Guardian Angels patrolling the streets of Caracas and Santo Domingo seems a bit far-fetched, one need only recall the derision and incredulity with which Curtis Sliwa’s original 13-member group was greeted back in 1978, when they began their first patrols. Sliwa has since proven himself to be much more than the overbearing, publicity-hungry charlatan portrayed by his enemies, and more even than the civic-minded do-gooder imagined by so many of his supporters. Already Curtis Sliwa has established himself as a man to be reckoned with in the world of American “alternative” politics. In a country where grassroots activism has long been segregated along starkly racial lines, Sliwa has forged a multiracial army of some 5,000 young men and women in 53 cities across the United States and Canada. He has successfully linked the traditional “white” demands for increased “law and order” with the seemingly contradictory agenda of neighborhood autonomy and curtailment of police authority once espoused by the black-and-brown-power movements of the Sixties.

That he has succeeded in selling this hybrid ideology not only to the mass media and the middle-American public, but also to such former inner-city militants as Felipe Luciano, ex-leader of the Young Lords, and Lester Dixon, an ex-Black Panther who now heads the Guardian Angels’ San Francisco chapter, is a tribute either to the unique timeliness of Sliwa’s political agenda, or else to his exceptional demagogic genius. Some critics have decried Sliwa’s “ambition,” accusing him of using the Guardian Angels as a stepping stone to a career in electoral politics. But it seems likely now that Sliwa’s actual program may be far more ambitious than that.

“Expanding into Latin America will be a very important step,” he promises. “We’ve already broken down a lot of barriers, a lot of prejudices here in the States, just by putting people side by side in those red berets and T-shirts and showing them that they can work together for a common concern. When we move into Latin America, we’ll start to break down even more stereotypes.”

And what then? Sliwa grows more vague when questioned on this point. Always at pains to deny any “ideological” slant to his organization, he is reluctant to enunciate any clear political agenda, at least for the time being. Yet, certain hints do slip out.

“Third World people should have a chance to determine their own destiny,” he says cautiously. “We’ve always stood for that. But we’re not like a lot of groups in the past. We don’t walk to the beat of color. We’re not out there just to protect black, or brown, or yellow, or whatever. We stand for everyone who’s disenfranchised, everyone who’s given up, who thinks there’s no way to fight city hall. Racism has always kept us from acting as a unified people. It’s only when we get over all that divisiveness that we can move on to other problems.”