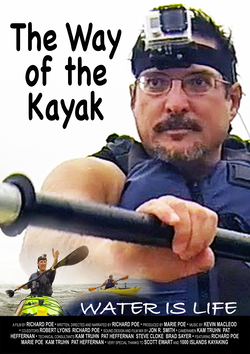

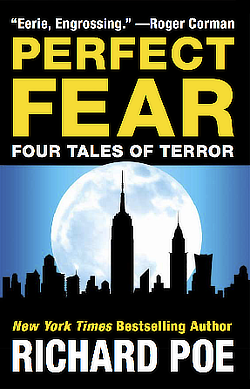

PERFECT FEAR: AUTHOR INTERVIEW, PART 3

A Conversation with Richard Poe, Author of Perfect Fear

by Paul Germano (continued)

| « PREVIOUS PAGE | NEXT PAGE » |

HORROR ON CAMPUS

Germano: When did you write your first horror stories?

Poe: I started writing short stories almost as soon as I knew my ABCs, probably in third or fourth grade. A lot of what I wrote as a kid was science fiction or dark fantasy, not exactly horror. In the seventh grade, I wrote a story in which the whole country is wiped out by botulism poisoning, and packs of wild dogs take over the streets.

Germano: So you really have been a fiction writer from way back.

Poe: Oh, yes. It was my life’s ambition to be a novelist. I only became a journalist later, when I needed a job. In fact, I majored in creative writing at Syracuse University, and graduated with honors in that subject. And when I returned for my master’s degree, in 1980, I once again chose creative writing.

|

POE: Each story in Perfect Fear contains… a secret, a different secret for each story. Each tale is a kind of psychological riddle. |

|

Germano: Geeze, we were both at SU at the same time. I graduated in 1980. That’s when I got my bachelors in journalism at the Newhouse School. We could have passed each other on the Quad!

Poe: I’m sure we did. We’re both about the same age. I guess I was a little ahead of you, because I skipped eighth and twelfth grades, so I was only 16 when I started college. But we were definitely on campus at the same time.

Germano: Did you write horror at SU?

Poe: We didn’t do horror in the SU writing program. They were training us to write fine literature, and horror was not considered literature. I remember writing a story at SU about a mild-mannered bank clerk who lost his mind when he started getting messages from a parallel universe. That was basically a horror story, but we had to call it something else. I remember talking through the problem with my writing professor George Elliott. He was very kind and eager to help, but he just wasn’t sure what to do with me. Eventually we decided that I must be leaning toward the Theatre of the Absurd, and that I should read more Samuel Beckett. But really, Beckett was not the right role model for me. Edgar Allan Poe and H.P. Lovecraft would have been more like it. But this was an academic writing program, and actual horror writing was not encouraged.

Germano: Yet you went back for more. You returned to SU to get your master’s degree in creative writing.

Poe: Yes, but it didn’t work out. I dropped out of graduate school after a year. Part of the problem was that, when I applied for my master’s, all of the fiction-writing slots were full, so I had to opt for poetry writing. So now I was writing poetry, and I just kept asking myself, how am I going to make a living at this?

|

POE: I learned more about writing in one summer at Naropa than I did in five years at SU. Many of the lessons I learned from Allen [Ginsberg], all those years ago, helped me to write Perfect Fear. |

|

I needed advice, so I went down to New York and met with José Angel Figueroa, who is one of the Puerto Rican poets connected with the Nuyorican Poet’s Cafe. A friend introduced us. José was very kind and gracious. He lived in this beautiful, high-rise apartment in Tribeca, with a balcony and a panoramic view of Manhattan and a gorgeous Puerto Rican wife, and I just couldn’t believe this guy wrote poetry for a living, and I blurted out, “How did you do this? How can you afford this?” And he said, “Oh, man, check it out. You gotta apply for these grants.” And he showed me brochures for all these lavishly-funded poetry programs which had been set up with help from the New York State Council on the Arts. José explained the whole system to me. What an eye-opener!

Germano: That was very generous of him.

Poe: Yes, it was! José gave me excellent advice. So I went back to Syracuse, as excited as a little puppy dog, with visions of Manhattan high-rises in my head. And I asked my poetry professor Hayden Carruth to help me apply for these grants. Hayden got very upset with me. He said, “Richard, you’re a real poet, and graduate school is no place for a real poet. You need to get out in the world and drive a truck.” And he basically told me that, if I spent my life sucking from the teat of these big-money foundations, my creativity would dry up.

Germano: Your own professor told you to drop out?

Poe: Yes, and I think he was right. Hayden was this grand old man with a beard, who had served in World War II, and I was this 21-year-old kid who had never done anything. Hayden was basically telling me that I needed to go out in the world and be a man. And I felt he was right. So I left graduate school after just one year, in 1981.

|

POE: In Perfect Fear, I explored my deepest fears and tried to bring them to life, so others could experience them too. Now, that’s kind of a strange thing to do, when you think about it. |

|

LESSONS FROM ALLEN GINSBERG

Germano: Was that the end of your academic career?

Poe: Not quite. Just after leaving SU, I did a writing apprenticeship with Allen Ginsberg, in the summer of 1981. Allen used to teach workshops at Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado. He was a great teacher. I learned more about writing in one summer at Naropa than I learned in five years at SU. Many of the lessons I learned from Allen, all those years ago, helped me to write Perfect Fear.

Germano: Which of Ginsberg’s lessons did you apply to Perfect Fear?

Poe: Allen believed in total honesty, total self-revelation. He believed that, if you wanted to write great literature, you had to pay the price. The price was exposing yourself to the world. You had to reveal some secret about yourself that you didn’t want others to know. Now, at the time, I lacked the courage to take that advice. I still lack it. But, after many years of pondering this question, I figured out that it wasn’t necessary to disgorge all your secrets in plain English. You could disguise them with symbolism and metaphor. As long as the secret was there, buried somewhere in the text, it still gave power to the work. Each story in Perfect Fear contains such a secret, a different secret for each story. Each tale is a kind of psychological riddle.

Germano: Were there any other Ginsbergian lessons that you applied to Perfect Fear?

Poe: Allen once told me that the purpose of his work was to make a graph of his own mind. He wanted to keep an accurate record of his own thoughts and perceptions, over time. And he did this for a specific reason. Ginsberg believed that our mission as writers and poets is to try to leave a record for future generations, so they will know who we were and how we thought about our world. Especially important to Allen was the question of the sacred. What sorts of things do people consider sacred, and how does that change, from one generation to the next?

|

POE: I started running up against fears and inhibitions. Writing horror activated certain fears. I wrote two horror novels… complete drafts, but couldn’t finish the final revisions. Both times, the fear kicked in, and I had to stop writing. |

|

Germano: What did he mean by sacred?

Poe: He didn’t mean it in a formal or religious sense. We all have certain things that are sacred to us personally, for example, old photographs of friends and family who are no longer living. Those things are sacred. And the older we get, the more sacred they become.

As we get older, our memories fade and the world we knew all our lives starts to vanish. We can’t preserve every memory. But we can try to preserve those bits and pieces of memory which are most important to us. We preserve those things which we consider sacred.

So our work as poets and writers becomes an act of historical preservation, and also a sacred act. We preserve a record of what we considered sacred during our lifetimes, and this becomes a message to future generations. It helps them to understand who we were. Allen believed that was important, and I agree with him.

Germano: What does Perfect Fear tell us about the sorts of things you consider sacred?

Poe: Well, in Perfect Fear, I explored my deepest fears and tried to bring them to life, so others could experience them too. Now, that’s kind of a strange thing to do, when you think about it. Why write about fear? And why my fears, in particular? I guess I did it because I consider my fears to be sacred. That would be Allen Ginsberg’s explanation, at any rate.

Reprinted from Perfect Fear (released by Heraklid Books, July 5, 2012)

| « PREVIOUS PAGE | NEXT PAGE » |