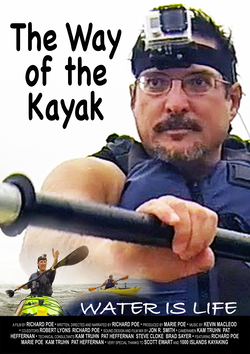

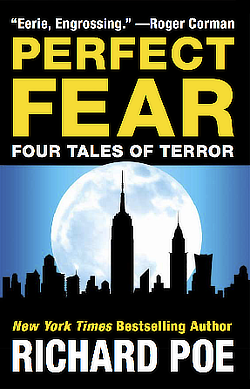

PERFECT FEAR: AUTHOR INTERVIEW, PART 5

A Conversation with Richard Poe, Author of Perfect Fear

by Paul Germano (continued)

| « PREVIOUS PAGE | NEXT PAGE » |

FAITH AND HORROR

Germano: As a Catholic, I also grew up with a strong appreciation for the Virgin Mary. When I worked at The Catholic Sun, I wrote articles in the late ‘80s on the apparitions that were going on in Medjugorje, in what was then Yugoslavia. I interviewed people from church groups who had gone over from the Syracuse Diocese and these people were truly inspired by the experience.

One man started crying during the interview. He told me that he actually saw the Madonna and she was so beautiful, and he just started to cry, in a joyful way. It’s amazing to think back. These apparitions started in 1981 and continued through much of the decade and the seers were saying that Our Lady was proclaiming the downfall of the Iron Curtain. And, amazingly, the Berlin Wall came tumbling down and the Soviet Union fell into history. I’m not sure how I feel about those apparitions, but it’s not something that can easily be dismissed or ignored.

|

POE: My mother had an intense fear of the demonic. …It went beyond anything she learned in church. I really don’t know where it came from. But it rubbed off on me. |

|

Poe: It took me a long time to understand the Virgin Mary. Even though I was born and raised Catholic, there was something about the Virgin Mary that I just didn’t get. Writing Perfect Fear brought me closer to her than I’ve ever been. And my wife has been a big influence. Marie is Greek Orthodox, and I think Orthodox Christians, in general, have a deeper devotion to the Blessed Mother than most Catholics do.

Germano: I notice that elements of faith pop up in your stories, for example, the soul in the computer in “The Strange, White Room” and the Virgin Mary protecting the little boy in “Don’t Come Back, Mommy.” Are those just natural parts of the story, or did you insert them in a conscious way, to give those stories a religious dimension?

Poe: Well, if you’re asking if I went out of my way to put a Catholic spin on these stories, the answer is no. I bent over backwards to avoid direct Catholic references. But certain issues couldn’t be avoided. “The Strange, White Room” deals with immortality, so it really wasn’t possible to confront that subject without mentioning the soul.

FAMILY GHOSTS

Germano: You told me in an earlier conversation that your mother disapproved of horror, and that you felt inhibited from writing horror, as long as she was alive.

Poe: Yes, that’s true. My mother died in 2007, God rest her soul. And I don’t think it’s coincidental that I’m finally publishing my first work of horror more than four years after her death. I think the two things are related.

|

GERMANO: It’s interesting that you would say you’re haunted by your mother’s disapproval, because you’ve written a story about a little boy who’s haunted by his mother. |

|

Germano: How so?

Poe: It goes back to the issue of maintaining a horror trance. In order to write horror, you have to reach down into the darkest places of your soul and dredge up whatever awful things might be lurking there. And you can’t be embarrassed or self-conscious about what comes up. You can’t be worried about things like, “Gee, I wonder what Mama will think when she reads this.” That sort of thought will kill your creativity.

Germano: What did your mother have against horror? Was it a religious thing?

Poe: I wouldn’t call it religious, exactly. My mother was Catholic, but there’s no rule against Catholics enjoying horror movies or horror novels.

Germano: That’s true. My parents were good Catholics, but they had no problem with horror. Watching horror movies on TV was a family event in our house.

Poe: Yes, exactly. My mother had an intense fear of the demonic. I’m sure there was a religious element to that fear, but it went beyond anything she learned in church. I really don’t know where it came from. But it rubbed off on me. Even now, nearly five years after her death, my mother’s disapproval still haunts me. I think I will always feel guilty about writing horror. But it’s so much fun. I can’t resist!

Germano: It’s interesting that you would say you’re haunted by your mother’s disapproval. Because you’ve written a story about a little boy who’s haunted by his mother.

Poe: Yes, that would be, “Don’t Come Back, Mommy.” That was one of the stories I couldn’t finish for a long time, because of fears and inhibitions. I began writing it in Montauk, in the summer of 1998. Marie and I had rented a place on the beach, and every night I would fall asleep listening to the surf thundering in the dark. So I started writing a story about a little boy whose mother drowns in the sea, and then she comes back as this horrible living corpse covered with seaweed and crabs and croaking like a toad. And I suddenly stopped and said to myself, “Richard, what are you doing? What are you writing? This is disgusting. What if Mama reads this, and thinks I’m writing about her? And what if she’s right?” And I just stopped writing it.

|

GERMANO: Are you related to Edgar Allan Poe? POE: No. My grandfather was born Rafael Aronovich Pogrebisky… My father was of Russian Jewish descent, and my mother was half Mexican and half Korean. |

|

Germano: At the end of that story, when the mother finally leaves and goes back to the sea, the closing line says, “and the crickets found their voice again.” When I read that line, I immediately thought, well, there’s Richard’s mother. Because you’d told me that you couldn’t write horror until after your mother died.

Poe: You’re right. I didn’t even think of that. Once the mother was gone, the crickets could sing.

Germano: I think the actual phrase was, “the crickets found their voice again.”

Poe: Yes, yes. Oooo. That’s sending chills down my spine!

Germano: [laughs]

Poe: Paul, you’re good. You’re good.

Germano: [laughs]

Poe: No, really. That’s good. I always liked that line in the story, but that particular symbolism never occurred to me. Very insightful! I think you may be onto something.

Germano: Thank you. Now I’m feeling a bit chilled myself, knowing that you didn’t realize that until I pointed it out. Okay, on to another question. This next one is obligatory. I have to ask it. So Richard, tell me, are you related to Edgar Allan Poe?

Poe: No. My grandfather was born Rafael Aronovich Pogrebisky. He changed his name to Ralph Poe in 1939. My father’s family were Russian Jews, from Kharkov and Grodno mostly.

Germano: So many immigrant families went through that name-change experience. Do you think you lost a sense of your own ethnicity with the Americanization of your surname?

Poe: To some extent, yes, but, in my case, the name change was almost incidental. I’m such a mixture of different ethnicities, they tend to cancel each other out. My father was of Russian Jewish descent, and my mother was half Mexican and half Korean. With a mix like that, it’s hard to speak of a sense of ethnicity.

HORROR IN THE HEARTLAND

Germano: Do you ever miss Syracuse?

Poe: All the time. I love Syracuse, and I always enjoy visiting there, at least during the six months of the year when it’s not winter.

Germano: In some ways, it seems you’ve become more of a New Yorker in your writing than a Syracusan. “Scotophobia” is a very New York story. You had to have a real sense of the city to write it.

|

POE: Stephen King is really the master. … King draws a lot of his power from his cultural roots, from the strong connection he feels to his people, his tribe, the small-town people of Maine. In addition, King is a gifted wordsmith. There’s a lot of poetry in his words. |

|

Poe: In “Scotophobia,” I was trying to capture the essence of what New York City means to me, so I put a lot of effort into evoking the feel and atmosphere of the city.

Germano: You left Syracuse in 1985, but has Syracuse left you? How much of Syracuse is still in your writing?

Poe: I lived the first 26 years of my life in Syracuse, so I don’t think I’ll ever lose my Central New York sensibility. Growing up there gave me a sense of the grandeur of New York State, with all its wildness and frontier history. I don’t know if you can really understand Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper if you’ve spent your whole life in Manhattan.

People in the city are very provincial, in their own way. They tend to stay within a hundred-mile radius of Times Square. They know Long Island and the Catskills, but they don’t really know the Adirondacks, the Thousand Islands, the Finger Lakes or Niagara Falls. Most have never seen Lake Ontario. They have no sense of the vastness and wonder that is New York State, and very little sense of New York’s Native American heritage, which is rich and fascinating.

It’s no accident that I made the hero of “Scotophobia” an upstater, because I’ll always be an upstater at heart, and I see everything from an upstater’s perspective, just as Frank Romain does.

Germano: Upstate New York is a very special place, I agree. So tell me, who are your favorite horror writers? Which ones had the biggest influence on you?

Poe: Of course, I read all the classics when I was young; Edgar Allan Poe, Bram Stoker, Mary Shelley, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu. And I read H.P. Lovecraft, somewhat later. But Stephen King is really the master. No one comes close to him. I love ‘Salem’s Lot, The Stand and The Shining. In my opinion, King equals and surpasses the greatest of the Gothic masters. His best works are his short stories. They deserve a lot more attention than they get.

Germano: Yes, Stephen King is amazing! What do you think is the secret of his widespread appeal?

Poe: King respects his material. He respects his characters. He respects their rural, small-town culture. He respects their fears. It’s all about respect, I think. King draws a lot of his power from his cultural roots, from the strong connection he feels to his people, his tribe, the small-town people of Maine. In addition, King is a gifted wordsmith. There’s a lot of poetry in his words.

In ‘Salem’s Lot, there’s a wonderful passage where the old drunk Weasel Craig starts reminiscing about a love affair from years past, and he free-associates very movingly in that rural Maine dialect that King knows so well. And, suddenly, in the middle of this soliloquy, Weasel exclaims to himself, “Ah God and sonny Jesus, time was like a river,” and it’s one of the most beautiful and breathtaking exclamations in all of literature. Every time I read ‘Salem’s Lot, I stop dead when I come to that line, just to hear those words reverberate in my mind, and to feel their power.

Reprinted from Perfect Fear (released by Heraklid Books, July 5, 2012)

| « PREVIOUS PAGE | NEXT PAGE » |